|

Texas Gal

by C. Sprite

Chapter Forty-One Didn't I Just Resolve That Problem?

As I opened my eyes, I realized that Nancy was standing over me. It was her gentle shaking of my arm that had roused me from slumber. "What…"

"I'm sorry, Miss Drake. You haven't been responding to the phone. I wanted to know if you need anything else before I leave."

"Leave?"

"Yes, Miss Drake. It's time to go home."

Nancy took a step back as I yawned and sat up on the couch. The wall clock indicated that it was ten minutes after five.

"No, I don't need anything, Nancy. The problem with the MoPacs kept me awake all last night. Thanks for waking me. You can leave now."

"Good night, Miss Drake."

"Good night, Nancy."

I tried to rub the sleep from my eyes as the office door closed behind her. I was glad that she had awakened me. If I'd slept much longer, I would definitely have trouble falling asleep later tonight. The nap had done wonders for me though. I felt much better, and I was even feeling a little hungry. Then I realized that I hadn't had lunch. I called down to Earl, to tell him that I was ready to leave, picked up my purse, and headed for the door while wondering what the Holiday Inn's restaurant was serving as their special tonight.

I was again able to smile pleasantly as I entered the office building on Thursday morning. I was well rested and very pleased with myself and my performance so far this week. Where I normally felt almost useless, I felt that I had made a valuable contribution this week, at least so far. I didn't know what I was going to do with myself for the rest of my two weeks I was here, but for now I was content.

I was on my second cup of tea, and my third trade magazine when Bob called and asked if I was available. I told him to come over. I could use a little company.

"Hi boss," he said, as he entered my office and strode over to where I was reading in the informal area. He placed his steaming mug on the coffee table and sat down in the overstuffed chair opposite my own. I could see the improvement in him also. We had both been a bit stressed out during the past few days.

"Good morning, Bob," I said. "Beautiful day, isn't it?"

"It is indeed. I got a call from John early this morning. The semi's with the crates from the Edger farm began rolling into Evansville yesterday afternoon around four o'clock and continued until after midnight. John said he couldn't believe that all the stuff they unloaded came out of one barn. He swears there must have two or three other barns behind the first."

I giggled as I imagined the look on John's face as truck after truck dropped its load off on the dock.

"He says that his guys worked most of the night. More than half the crates have been opened. Any crate that definitely couldn't contain anything related to a binding machine, was sealed back up and moved to the furthest point in the warehouse. But not until the crate was numbered and marked with exactly what was inside. Machine make, model, and serial numbers were all recorded. Unfortunately, that only accounts for about half the crates. The rest are still spread out in the warehouse like a giant erector set while they try to figure out what is what."

"Poor John," I said.

"Poor John? He's having the time of his life. He seems to be grousing a bit, but I know him. It's a challenge he wouldn't walk away from for love or money. He's an engineer's engineer."

I smiled at the mental image of John up to his ears in machine parts, and loving every minute of it.

"I also made arrangements for the five new machines from Lassiter," Bob said. "Myles Freeman, the Lassiter Exec VP, was positively red with rage. I couldn't see him, but I could feel the heat of his anger through the phone in every word he uttered. He said that he'd had to immediately cancel shipping arrangements for all the 6130 models ready to go out, and then shuffle all orders in-house to work us into the delivery schedule. He said that other customers would have their delivery dates pushed back by as much as two months."

"They only make five machines a month?"

"Of that model, I suppose. Most of their production centers around machines that bind with glue, both hot and cold. But that's no good for notebooks because they can't be opened flat. It's used for paperback books and such."

"But the five machines will be ready for shipment on Friday?"

"Yes."

"Wonderful. But why do you suppose they had five completed machines sitting there if they only produce five machines a month and have ten months of backorders?"

"Some manufacturers like to keep a real deep cushion under themselves, in case something happens where they need product immediately. It's like a restaurateur who always keeps one or two tables reserved, even when they are most crowded and people are waiting to be seated. If someone very important drops by, they can immediately be seated rather than having to wait. I know that it might be silly to some, but it's the way things are in the business world. Perhaps for Lassiter, five machines is their 6130 cushion. Freeman might be most angry because we yanked his cushion out from under him. It might take months to rebuild it. Anyway, the Lassiter plant in Terre Haute is only about a hundred twenty miles north of our Evansville plant, so I've arranged for one of our trucks to go pick up the machines. Three will be dropped off at Evansville and the others will then be driven south to the Little Rock plant. We have more than enough space at those plants for the operations on a continued basis, and there's a good supply of local labor. Little Rock will have their machines by Monday morning."

"Good. Very Good. I trust we'll have the space ready for the machines when they arrive, and people ready to set them up?"

"Taken care of. Both plants have already begun to prepare the space."

"And we'll have wire supplies and spare parts ready?"

"Wire, yes. I don't know what spare parts we'll need. We have no experience with that equipment."

"We're going to have ten machines of the same model. At some point motors and bearings will seize or burn up, and belts will break. I'm sure the parts people at Lassiter will be able to tell you which parts have had to be replaced most often since the machine went into production four years ago. Let's get some of the more common replacement items, just in case. We can't afford to have any of the machines down while we wait for parts to be shipped in. I can imagine a problem occurring on a Friday night after Lassiter is closed. We won't be able to order the part until Monday, and then won't receive it for another two or three days. We could lose an entire week of production."

"Okay, boss I'll call right away. Ordering some spare parts shouldn't affect their shipping schedule for new machines. Where should we send the other machines when they're ready?"

"I was thinking that Franklin would be a good place. We have tons of room there, and although we haven't been making paper yet, the plant is up and running because the boxing operation is going full bore."

"Good idea. I'll arrange to have covers and ruled-paper shipped to Franklin so they'll be ready when the machines are set up."

"That'll give us three locations capable of producing the notebooks. We'll be able to continue production in case there's a problem at one of the other plants."

"What kind of problem?"

"Oh, I don't know; strike, flood, fire, whatever."

"Flood?"

"Nine of our paper plants are located near the Mississippi or Ohio rivers. I gave a lot of thought to flood damage when I was considering the Mo Paper purchase. It's probably not a question of if those rivers will flood again, but how soon."

"And I was having such a good day," Bob said mournfully.

I giggled. "I'm sorry. I wasn't trying to be a downer."

"No, you're absolutely right. We have to consider the possibility of having nine plants flooded out at the same time. All of the finished product in the warehouses would be ruined instantly."

"In addition to building the sediment pools, we should consider building some sort of a levee around those plants in danger."

"First we should determine exactly which plants are in danger, and the cost of constructing the levees. Have you visited any of the plants?"

"No," I said, "not yet, except for the new plant in Jefferson City."

"I visited each of them before we made the final decision on the plant closures. Of the nine plants located in cities and towns along the Mississippi and Ohio, only one is actually located very near the river. The other eight are located on tributaries. I can practically guarantee that four of them never need fear flooding because of their height above the average river flood level. The plant at Evansville, for example."

"That sounds encouraging. But we should have engineering companies in each area prepare damage probability reports just the same."

"Okay. I think that's a good idea. I'll arrange for them."

"We should also start to think about the construction of sediment pools like the system at JC."

"Okay. I'll include that in the specs as a Phase II."

"Good. Well, is there anything else?"

"Just one thing," Bob said. "We've taken orders for another twenty million notebooks."

"Another twenty million? You mean in addition to the twenty million that had already been ordered?"

"Yep. A lot of them were from the same people that had ordered originally. We had called to tell them that we would be sending them staggered shipments as the notebooks were produced. I then had our people start calling again, after I had confirmed the shipment of the ten binding machines, to tell the customers that they would be getting their entire order in August after all. We told them that instead of spreading out the shipments to everyone who ordered, we had rethought our position and decided to fill the orders in the sequence they were received. I guess a lot of people thought they might not be able to get reorders very quickly, so they asked to double their initial order of the MoPacs."

"So we have orders for forty million notebooks?"

"So far. Do you want to cut off accepting new orders?"

"Let's see," I said, as I scribbled on a piece of scrap paper. "The new equipment can produce 2.16 million notebooks a month, if we keep it busy twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. We know there will be downtime, so let's figure a maximum of 2 million a month. The five machines being shipped will be able to produce 20 million notebooks in two months. The other five won't be received for thirty days, so we'll only be able to produce 10 million more by August. The machine that I just purchased from Mrs. Edger can produce 2 million notebooks by August. That leaves us 8 million short. And here I thought all our problems were over."

"We'd better stop accepting orders."

"Yes— No. Let's just stop accepting orders calling for full shipment in August. Tell the new customers that twenty-five percent of their notebook orders will be shipped by mid-August, with the balance in September. Once we fill the present orders, we'll be able to produce 21 million notebooks a month. But if orders continue to mount faster than our ability to handle them, we'll have to delay the delivery date until October. We should be able to handle reorders after that."

"New MoPac orders have started to slack off a bit, so that sounds reasonable. I guess that most school supply orders for the new school year have now been placed."

"I don't know whether that's good or bad," I said.

"It's mixed news, I guess. We're out from under the guns, but it's great to be fighting to keep up with demand. It's not a problem that we've ever had before."

"You know, I've been agonizing over this problem for days and I haven't even seen any of the notebooks yet."

"Oh, that's right. You didn't see the samples that we got from the first run."

"Who has them?"

"They're all gone."

"All of them?"

"Yeah, we handed them out to our employees a month ago when we thought the project was a bust. But then when I brought several home, and my kids loved them, I started to figure that we really had something after all; we just hadn't marketed it properly. I was trying to figure out how we should promote them when the tidal wave of orders hit."

"I guess I'll have to wait then."

"I'll have some sent up from Evansville as soon as they start production. We should have some here anyway, to respond to requests for samples from our customers. We should see them next week."

"Good," I said. "I'll be able to get a few before I head home again."

"I guess I'd better get going," Bob said, looking at his watch. "I have a meeting with the Picnic Committee to review the details of our annual fun fest."

I smiled. "Anything I can do?"

"No. The details were all set six months ago. This is just a final review. I don't expect it to last more than ten minutes."

"Okay, Bob. I'll see you later."

"Right, boss."

I returned to my reading after Bob left, but a lot of the news in the latest issue of Paper Press was boring stuff. There was a reprint of an article on root fungus from an agronomy magazine, and an article on new developments in printing inks. I flipped through the magazine until I came to the section about personnel moves in the industry and read about the promotions, transfers, and new hires and fires. They don't actually call them firings, of course, they call them resignations. But most of the time they amounted to people being offered the opportunity to resign before being discharged, if they didn't have a job to move into.

I was brought up short when I saw an article about Benjamin E. Chamberlain, the CEO of South-Core. The news blurb said that Chamberlain, aged 61, had decided to retire from the company he had built from a single plant operation in 1937 to the highly successful operation that it was today, with paper plants, cardboard plants, a formed-paper products plant, and large tracts of forest land. The article said their operations stretch from Maine to North Carolina. I half expected to see my name mentioned since South-Core and I had been linked so often in the press, but they said nothing about me. I wondered if the new management team would continue the old practices, or end the dirty tricks and shady practices employed during Chamberlain's rule. Mostly I wondered if they'd finally stop targeting me. If they didn't, I would continue to upset their nefarious plans at every opportunity. They would be far better off leaving us alone.

After lunch I continued to read and relax. I knew that we would fall short of promised notebooks, but we had plans in place to fill most of the orders and I just needed to think about something else for a while. Just after three o'clock, I got a call from John, who was still in Evansville.

"Hi, John. How goes the effort?"

"We've made good progress, DD. For the past five hours I've been setting up the Lassiter wire coil binding machine. We've been testing it and making minor adjustments while we've been training the operators. I think that we're about ready to go into production. The first batch of covers arrived from Bloomington last night, and the paper arrived from Little Rock this morning. We've got a whole staff of operators standing by to start production any minute. My guys are just getting our tools and stuff out of the way so that the area is clear and ready. I thought you'd want to know right away."

"Thanks, John, I did. You've done a wonderful job."

"My pleasure, DD. This new Lassiter is great. The manual is well written. It gives exploded views of every part of the machine, and it was just a matter of fine-tuning it."

"New Lassiter?"

"The Lassiter 6130."

"You weren't supposed to get those until late Friday or early Saturday morning, but I'm glad they arrived early."

"Friday?"

"Yeah. Bob told me that he was sending one of our trucks to Terre Haute tomorrow to pick them up."

"I'm talking about the Lassiter you purchased from Mrs. Edger."

"We got a 6130 from Mrs. Edger?"

"Yes. It's brand new. Well— at least it's never been used. It was still in the original packing crate from Lassiter."

"A 6130?"

"Yes."

"I thought that we were getting a 4515a-25 from Mrs. Edger."

"I've found replacement parts for a Lassiter 4515, but when we uncovered the Lassiter 6130 we immediately began setting it up. Do you think that there's a 4515 also?"

"That was the model number on the owner's manual that Mrs. Edger showed me. She said that her husband had been saying for years that he was going to get a new, much faster machine, but then he was diagnosed with Leukemia. Perhaps he purchased the new equipment just before being diagnosed and never set it up."

"Whatever happened, we have a new 6130 about ready to go. As soon as we start production, I'll take my guys back out into the warehouse and see if there's another Lassiter in any of the crates we haven't fully unpacked. There's an incredible amount of stuff out there. Mr. Edger must have had a terrific printing business."

"Okay, John. The new 6130s from Lassiter should be there by Saturday at the latest. Better get some rest so you'll be ready to set them up."

"We'll be ready, DD. By Sunday we'll be running flat out here, and we'll be ready to head to Little Rock to set up the other new machines."

"Don't overdo it, John. We don't want anyone getting hurt because they're overtired."

"Don't worry, DD. We'll get our rest."

"Okay. Thanks, John. And thank your guys for me."

"Will do. Goodbye, DD.''

"Bye, bye, John."

We were in better shape than I'd thought. The 6130 was twice as fast as the 4515. That meant that we should be able to produce an extra two million notebooks by August above what I had calculated. That still left us 6 million short, but if there was also a 4515 in the equipment we had purchased from Mrs. Edger, our deficit would be reduced to just 4 million. I felt good enough to prepare another cup of tea for myself.

On Friday we held the regular weekly meeting in my office. Neither Gerard nor Ron were there, but they would attend the meeting next week. With John's absence as well, the table seemed empty.

"Bob," I said, after everyone had prepared their beverage and taken their seat, "would you like to start us off?" I realized it was a silly thing to say. Bob, as the Exec VP, always started us off when I didn't have any comments to make at the start of a meeting.

"It's been a good week," Bob said. "Sales of MoPacs have climbed through the roof, and pulled other sales up with them. Last year, Mo Paper had an estimated .009% of the U.S. market with its sale of 58,500 notebooks. So far, we've garnered almost seven percent of the entire projected annual U.S. market with our sales of more than 4 million MoPacs. That's an impressive improvement in anybody's book. Together with sales of our other new items: specialty napkins, inexpensive Kraft envelopes, and very colorful but low grade construction paper and notepaper, we're actually struggling to meet demand. Of the twelve plants closed after we took possession of MoPaper, we've either reopened, or are in the process of reopening, eight. I didn't really think that we'd need to bring that many back on line this year, but their older, slower equipment is well suited for the products we're making in them. Actually, we could probably use all the plants right now, but I don't want to open them and then have to close them again after the initial demand for new product is over. So we'll run the reopened plants in overtime until we see if the demand for these products continues. That's all I have to say."

"Wonderful news, Bob. Bill?"

"We're busy training the people in the reopened plants to use our reporting systems, and they're coming along well. We've collected a good amount of the outstanding A/R we inherited from Mo Paper with the takeover, but had to write a little of it off as being uncollectible. Everything is running smooth."

"Thank you, Bill. Ben?"

"We're busy as heck with the rehires, but I'd rather be bringing people back than laying them off. The folks in the communities where we closed the plants are ecstatic that the plants are reopening. I think they finally believe that we were being honest when we said that the closure was to overhaul the equipment and have it ready when demand for product picked up. We've been getting a lot of calls from people in the communities where plants remain closed though, asking us when their plant is reopening. They see other Mo Paper plants reopening and are afraid that we might be phasing out their plant. We continue to tell them that market forces dictate the demand for product and we're doing everything possible to improve MoPaper sales so that we'll need the capacity offered by their plant."

"Thank you, Ben. As Bob said, we don't want to open plants and then have to close them again. We'll reopen the plants when we're sure that our demand isn't simply a flash in the pan. Tom?"

"We've been kept pretty busy the past week, making sure that each of the reopened plants has the supplies it needs, but it should taper off a bit now. I'm pleased that we're able to bring them back on-line."

"Thank you, Tom. Matt, I've saved you for last."

"Thank you, DD. In all my years in the paper business, I've never seen a phenomenon like this. Since my sales teams missed lunch several days because they were too busy taking orders, each sales office received a catered lunch yesterday, courtesy of you. You'll get the bills next week, DD."

"Thank you," I said, then smiled.

"Don't mention it," Matt said. "Seriously, we've had a wild ride during the past week. When no orders came in after we mailed the catalogs and shipped the samples, I thought that the project was a flop. I know now that we just shocked the buyers so much they had to think about it for a while. When they started to hear about the reception of the MoPacs in the college bookstores, the dam broke and we've been flooded with orders. Taking orders, in just a week's time, for enough product to account for 7 percent of that item's annual sales in the US by all producers, may be something we'll never see again in our lifetimes. I'm proud to have been a part of the team that developed the MoPac. Its success can probably best be evidenced by the rumors that a half-dozen other notebook producers are rushing to develop their own flower-power covers, and promising that they can deliver by mid-August. But we'll always be known as the company that introduced this innovation, and all others will be labeled as copycats. If there's any doubt, we have the orders to prove it. If Mo Paper wasn't in the mind of every school supply buyer when it was time to order supplies before, it is there now.

"Our other new items have also been very well received. Perhaps we shouldn't even be calling ourselves salespeople right now, because the items are selling themselves. We've been relegated to mere order-takers this past week."

"Thank you, Matt. We appreciate the wonderful way that your people stepped up this past week and met the challenge. As far as I know, everyone who tried to order was able to get through, as the phone calls to JC rolled over to the other toll-free lines and the salespeople in all three regional offices became order takers for a week. As for being mere order-takers, it isn't true. Your people designed the products and produced the catalogs that are selling it, even if the skills of our telephone sales folks don't come into the equation right now. Should one of your graphics people be singled out for an employee award such as dinner for them and their spouse at a nice restaurant?"

"Deborah had three of her designs selected for the MoPacs, but all the artists worked very hard. I think that we should treat them all to a nice dinner."

"Very well. Pick out a few restaurants and make arrangements with the owners for a nice dinner for each artist and spouse, or friend if they're not married, to be charged to the company. Make sure that Deborah gets her pick first, and then the other designers of 'winning designs,' before the rest get to select their restaurant."

"Will do, DD."

"At the beginning of this week," I said, "I was racking my brain to find a solution to a problem. We'd taken orders for five million notebooks, and I'd just learned that the binding equipment which we'd gotten as part of our acquisition of Mo Paper would only be able to produce one-million eighty-thousand notebooks before the promised delivery date. That would leave us more than 3.92 million notebooks short. I began an immediate search for more binding equipment, but every effort produced a dry hole. To make matters worse, the orders continued to flood in, and by Wednesday we needed twenty million notebooks, while our output hadn't increased at all. It was only through good fortune that we were finally able to secure most of the equipment that we need.

"John Fahey has been working almost constantly for two days to get the equipment set up and operating, and he expects to be at it for four or five more days yet. It's the hard work and dedication of our management teams and employees that have made this company prosper. Thank you all for your Herculean efforts. Our little company isn't so little anymore, and continues to grow by leaps and bounds. Its success is owed to each and every one of you. Alliance Paper better watch out, Piermont is moving up."

There was a chuckle all around the table; probably because Alliance was an international company ten times our size. But when I first purchased the Brandon plant, Alliance had been four hundred times our size.

On Saturday, I flew down to Teterboro Airport in New Jersey. Located about five miles west of the George Washington Bridge that spanned the Hudson River into New York City, Teterboro was one of the sites where the FAA administered the written part of the private pilot exams. I had memorized Auntie's flight manual from cover to cover and I felt I was ready.

I was more nervous when I sat down to take that exam, than when I negotiated million dollar deals. I worked to get my breathing under control and had calmed considerably by the time the test booklets were handed out.

As we traveled back to Vermont that afternoon I felt good. I knew I had aced the exam. Auntie had insisted that I pass the written portion before I started taking flight lessons with a certified instructor, so as soon as I got my papers from the FAA, I could take to the air. Although I also had my learner's permit for driving a car, I'd only had one full day on the ranch before leaving to come north and hadn't had an opportunity to get behind the wheel with either Mother or Auntie in the car. Both Judy and Mary had their driver's licenses, but Mother insisted that she or Auntie be with me for my first few lessons. I wondered which license I'd earn first.

Back at the Holiday Inn I was too excited to concentrate on the books that I had brought home from the office, so I went for a long walk after dinner and then relaxed in a chaise lounge by the pool as I watched the sunset. The exercise and relaxation had the desired effect and I awoke Sunday morning feeling fresh and alert after a deep sleep.

I lay out by the pool all afternoon, still trying to figure out how I was going to produce the millions of notebooks that we still needed for August. The days were going by fast and August would be here before I knew it. I got a light tan, which I needed as a base for my upcoming trip to the Riviera, but I was no closer to a solution when the day was over.

As I stood staring out the window of my office on Monday morning, I received a call from John Fahey.

"Good morning, John," I said as Nancy made the connection. "How's the weather in Evansville?"

"As far I know, it's good, but we're in Little Rock now."

"You finished installing the new equipment in Evansville?"

"Not just the new equipment, DD; we found the Lassiter 4515 that you thought was in the stuff from the Edger farm and set that up as well. There was a small problem with the conveyor belt, but we were able to fix that. The old man must have bought the new machine after the old one experienced problems because the belt was brand new. But the problem wasn't the belt, it was a seized bearing. We rummaged through all the 4515 parts and found one. The old man had a good supply of the things most likely to fail; he just diagnosed the problem incorrectly."

"Wonderful. So you have it working fine now?"

"Like the day it was first set up. When we left, the operators at Evansville were turning out notebooks at a prodigious rate. My guys are unpacking the new machines down here and we'll start installing them shortly. The folks here cleared a large area for us to work, and we can really spread out and get the job done quickly. After having the experience of setting up the other three machines, we'll fly through the install here. Our experience with the other machines will help us lay out the area so the space is used to the best advantage."

"That's wonderful, John. You've lifted a huge weight off my mind."

"I should be back in Brandon on Wednesday."

"After you and the guys finish down there, take the rest of the week off and relax."

"I have some stuff that needs to be looked at, but I'm sure my guys will appreciate the time off."

"They've earned it. I really appreciate the effort they've put forth for Piermont. I'll see you at the meeting on Friday then, if you're around."

"I'll be there, DD. See you in Brandon."

I was smiling as I hung up the receiver, and breathed a huge sigh of relief. Although just half the speed of the new machines, the 4515 was a very welcome addition to the binding production effort. Now we were only going to be short 4 million notebooks come August. A mere pittance compared to the shortfall I was expecting just half a week ago.

I spent the next twenty minutes brainstorming the problem. On a sheet of paper I wrote down everything I could think of that would solve our shortfall, including the possibility of farming the job out to a company that specialized in binding books. When I felt that I had listed all possibilities, I began examining each and listing why it might be a good solution, or why it was a terrible idea, i.e. the pros and cons of each solution. Most of the cons involved expense, since most solutions would raise the cost per notebook to as much as three times our wholesale charge to customers. While equipment expense is initially high, cost is spread out over the useful life of the machinery, with the pro rata cost per notebook produced being miniscule. When I was done, I hadn't made a decision, but I had a page full of scribbled ideas.

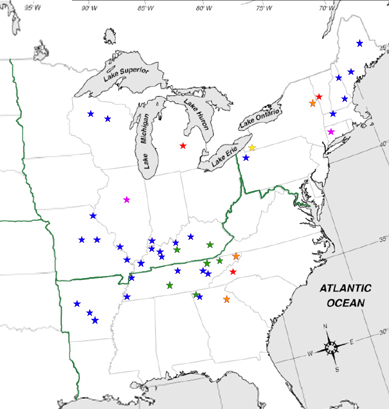

My head ached and I needed a break, so I took out the map that I had made at the ranch; the one that plotted the location of all Piermont plants. Using the same small stars I had originally used, I added a star for each of the Mo Paper plants we had added to the division. I deliberated whether to use a different color to denote the plants still closed down, but then decided that the situation could change at any time and I didn't want to keep changing the map around. I might have to do that anyway the way I kept buying plants.

When I was done with the map, it looked like somebody had sneezed stars at it, because the new Mo Paper locations were tightly clustered in a four state area, with the other Piermont locations distributed more evenly over the eastern part of the U.S. Seeing the completed map gave me a different sort of perspective of the company. With the purchase of Mo Paper we had almost doubled in size overnight, the hoped for goal of South-Core when they began their sneaky take-over attempt. With four of the plants still closed, I wondered for the first time since I began building the division if perhaps I shouldn't sell some plants.

|

|

The four plants that remained closed were the oldest in the company, and had the oldest, slowest, and least efficient paper making equipment. It appeared that Roy Blu had purchased everything that came along, basing all his business decisions on initial cost while ignoring plant efficiency and other factors. I didn't feel for a second that the purchase of Mo Paper was a bad decision, but these four plants would never be more than marginally profitable with just one shift. Overall, the valuation of the plants had been accurate. We did pick up $228 million in assets for $70 million, after discounting the Alabama plant and supplies that I'd deeded back to Roy Blu. I was only thinking that the money tied up the four plants might be better invested in newer plants with newer equipment.

When Bob Warren dropped by after lunch, I told him my thoughts.

"You might have a point, boss," he said, "but we should hold off making any decisions right now. We might need the paper making capability this year."

"Franklin hasn't even begun making paper, Bob. Once it ramps up, it'll be able to out-produce all four of the closed plants combined, by a factor of three."

"Is this line of thought related to our discussion about possible flooding?"

"Uh, I suppose that affects it a little. All four plants are located in flood plain areas, as the map clearly shows."

"I understand, but perhaps we should wait until we get the reports from the engineers looking into the possibility of flooding before we get to the point where we're making any decisions like this?"

"You're right" I said. "We'll hold off until we get the final reports you ordered. What else is happening?"

"I spoke to John. He told me that he called you this morning."

"Yes. I told him to let his guys have the rest of the week off after they finish getting the equipment installed in Little Rock. He won't take any time off himself. He says that he has too much to do."

"I know. John is sometimes too dedicated. He hates to take time off. It's like he's afraid that he'll miss something if he's gone for a few days. He's been calling his people here twice a day since he's been in Evansville."

"I think it's time we gave him a new title. Maybe it'll give him a little greater sense of security. He and Tom Harris are the only members of our top management that haven't been made Vice Presidents."

"Good idea," Bob said.

"Both Gerard and Ron will be here on Friday for the weekly meeting. I'll announce it then. Next month I'll do the same for Tom Harris."

"They both deserve it," Bob said, nodding. "So what's next, now that we've hurdled the problem of assimilating Mo Paper?"

"Have we?"

"Haven't we?"

"I'm still projecting that we're 4 million notebooks short of our sales calling for August delivery."

"Maybe, maybe not."

"What do you mean?"

"The new machines are each capable of binding 2,160,000 notebooks a month. You've only allowed for 2 million. That leaves an extra 2,720,000."

"2.16 million is the optimum production. It's unrealistic to plan on those achieving those numbers."

"Perhaps, but maybe we can plan on 2 million extra? Most of the binding machines are brand new after all."

"That's true."

"So all we need is one more machine like the Lassiter 4515 to produce everything we need."

"Yes," I said a bit suspiciously. I hoped that I understood where this conversation was going.

"So, knowing that, I spent the last four hours having my secretary call every large print shop in the country."

"And?"

"And— we've found another Lassiter 4515 for sale."

"You did?"

Bob nodded. "It's in San Francisco, at a company called Bay Binding and Printing. We can have it next week, after their new 6130 arrives."

"Ut oh," I said.

"What?"

"After their new 6130 arrives?"

"Yeah?"

"Bob, have you forgotten? We got all the new 6130's ready to be shipped."

"Good Lord. I wonder if we got their machine?"

"One way to find out."

"Call Lassiter?"

"Yeah," I said, "but you'd better call. I don't know if Gilly wants to hear from me again for a while."

"Okay, I'll call Myles Freeman. He probably won't want to speak to me any more than Lassiter wants to speak to you, but I'm sure he'll take the call."

"We're just a couple of persona non gratae, I guess."

"Maybe," Bob said. "But I couldn't be in better company."

I grinned and said, "Me neither."

Rather than lay around the office for three days, I decided late Monday to conduct a whirlwind inspection tour. I didn't really intend to inspect anything very closely, I just wanted to see the new plants for myself. I knew that after we returned from the Riviera, I wouldn't have the jet at my sole disposal. Susan was scheduled to begin a month and a half round of inspections of forestry lands and sawmills, so we would have to coordinate our use of the plane.

We took off on Tuesday morning while it was still dark and landed in Evansville just as the sun was coming up. Nick Nolan, the plant manager, was waiting for me, to personally drive me to the plant. The parking lot was almost empty because, other than the round-the-clock binding operation, we were only running one full shift with two additional hours of overtime.

We took a quick walk through the plant so I could see what I had bought and wound up at the binding operation. John had been correct when he said that notebooks were being produced at a prodigious rate. They were flying through the machines. The operators looked weary after a long night of trying to keep up with the capacity of the machine, but the shift was almost over and they'd be able to collapse into their beds soon. Nick told me that the operators would work for an hour, and then get a fifteen minute break, throughout their entire shift. They operated in relays, like runners in a race. When it was time for a break, a rested worker would jump in as the other worker stepped out of the way. The machine never stopped and the workers managed to keep up with it somehow.

In the warehouse, pallets of notebooks were piling up quickly. Nick said that as the plant ramped up paper production, they might have to consider shipping notebooks to other facilities to make space for the completed paper rolls. I told him that we'd do that if it became necessary, but that I'd chosen Evansville for the binding operation because of the enormous warehouse.

I asked Nick to bring a couple of cases of notebooks to the plane when we left, and he gladly complied. He said that a dozen cases had already been shipped to Brandon, and each of the regional sales offices so they'd have samples for customers. I thanked him for picking me up and giving me a tour of the plant when he dropped me off at the plane. He in turn thanked me for buying Mo Paper when I did. Like many of the plant managers, he'd seen the writing on the wall for a year as production quotas were continuously lowered and people were furloughed. He had expected to be out of job before the end of the year.

My next stop was the plant in Canton, Missouri. The first shift was well into the morning's production run when I arrived, and I was in and out in an hour. The plant manager wanted me to stay for lunch, but I told him that my time was very limited and that I'd have to take a rain check.

I had promised Ian Thorehill, back when he was still at the Ashville plant, that I'd see him once school ended, and I wanted to keep that commitment. The plane landed in Jefferson City about eleven o'clock and a person from the plant was waiting at the airport. Ian rushed to greet me as soon as I entered the front doors of the gleaming facility.

"DD, welcome to Jefferson City," Ian said as he hurried towards me.

"Thank you, Zit. I'm happy to be back again. I hear that you're doing a tremendous job here."

"It's been an exciting time, DD. Thanks for giving me this opportunity."

"I didn't give you anything, Zit. You earned it. I'm sorry for the alienation from your family that being loyal to Piermont has cost you."

"And I'm sorry that some of my relations are ignorant boneheads who blame me for their troubles because I refused to act like a jackass and support their wildcat strike in support of family members who wanted to collect a paycheck for not working. That kind of thinking is responsible for us losing Appalachian. They'll never learn. Well, it's behind me now. I love my new job and I'm even beginning to warm to Jeff City."

"Wonderful," I said, "on both counts. I was afraid I had heaped too much on your shoulders."

"Not at all. It's been great. This new plant is incredible. It's worth every penny of the thirty-two million it cost to build."

"Yes. Roy Blu said that he intended it to be his crown jewel. It turned out to be a crown of lead, though, for Mo Paper. The cost of building it dragged down his entire company."

"That was a shame. But a lot of people had advised him to slow down and postpone construction until he saw an upturn in sales. He ignored all the warnings."

"Roy's an optimistic and aggressive entrepreneur. I have no doubt that he'll be on top again. Probably a little wiser next time. They say that nothing teaches success like failure. Most of the top business people experienced a failure or two. They get back up, dust themselves off, and plow ahead again, a little or a lot wiser."

"Have you experienced any failures, DD?"

"Not yet," I said. "But I'm always looking over my shoulder. It's bound to happen sooner or later. I thought that I had when we took orders for twenty million notebooks and couldn't find a way to produce them on time. I could already see the headlines in the Paper Press every time I tried to shut my eyes and fall asleep. I guess I lucked out again."

"I think that Darla Anne Drake makes her own luck. It's like that old saying, 'When life hands you nothing but lemons, make lemonade.'"

"If only it were that simple. Come on, we can talk as we tour. I still have fifteen more plants to visit by Thursday night."

I had seen the Jefferson City plant on the day I bought Mo Paper, but it wasn't in operation then. It looked vastly different now. The state of the art paper forming machines were running full bore. And they were running that way twenty-four hours a day, except for down-time for preventative maintenance. Since the equipment was still like new, downtime was minimal right now. A dozen semis were being loaded with paper products, while several railcars were receiving similar treatment. The paper was flowing from the plant as fast as the machines could make it. It was an impressive sight.

|

|

I stayed to have lunch with Ian and then had him drop me off at the plane on our way back from the restaurant. I always enjoyed visiting with him, and wished that I had more time, but he had a plant to manage and I had a lot of inspections ahead of me.

I managed to tour all eighteen of the new paper plants by Thursday night. I would have liked to visit the Alabama plant that we had sold back to Roy Blu, just to say hello, but simply didn't have the time.

I'd felt good about the purchase of Mo Paper from the beginning, but felt even better after the tour. The nebulous feelings I'd had from not seeing the plants first hand before the purchase had completely dissipated. Whenever I thought about a particular location now, I'd have a firm image in my mind of the plant there. If I'd taken the time to tour all the plants beforehand, I might have lost the deal to South-Core.

We had a full house for the Friday meeting and kicked it off at ten o'clock. Everyone had already prepared their beverage of choice and was ready to begin.

"Good morning, everyone. Welcome to our weekly meeting. We have quite a bit to cover, so let's have it. Bob?"

"We've had a tumultuous two weeks. I won't talk about the enormous success of the MoPacs anymore, other than to say that we continue to accept orders and continue to have delivery deadline problems. We're currently promising mid-August delivery of twenty-five percent of all orders calling for immediate delivery, and although they've slowed considerably, they're still coming in. Presently, I fear that the purchasers are trying to do an end run around us. The orders we're seeing are far larger than I would expect from certain buyers. I suspect that they're ordering four times as many MoPacs as they really want, with intentions of canceling the undelivered balances after receiving the first part of their order.

"At the beginning of this week, we were in a position of only being unable to deliver two million notebooks. That number has climbed to almost twelve million. I thought that we had found another binding machine, but it turned out to be a dead-end. The machine would have been shipped to us as soon as the company received their new 6130 from Lassiter, but it turns out that thanks to DD's inspired maneuver, we've received their 6130. It's already been setup and is operating in either Evansville or Little Rock. The company in San Francisco can't release their used machine until they have one to replace it. Since we've been promised the next five 6130's manufactured, the order going to them has been pushed back.

Other than the problem with delivery of the notebooks, everything is going great. Orders for existing and new products in the Mo Paper lines have skyrocketed right along with the notebooks. If we could solve the notebook delivery dilemma, I'd be able to sleep peacefully at night. We've confirmed that several of our competitors in this market are promising flower-power knock-offs for mid-August delivery, although they don't even have samples ready yet."

"If we have to disappoint any of our customers," I said, "it's all my fault. Bob wanted me to have our sales people refuse additional orders calling for mid-August delivery but I didn't. I thought that the big crunch was over and that we'd find a way to produce the notebooks. Matt, take care of that today please. No more orders calling for mid-August delivery. Let our competitors have the business of anyone that can't wait until mid-September."

"Right, DD," Matt said.

"What about the orders that we've already taken?" Bob asked.

"I'll get busy on it and figure something," I said. "Don't ask me what, but I'll find a way."

I hoped that I sounded more sure than I felt.

"Let's continue on with the reports. Gerard?"

"Midwest is doing great. Ian Thorehill has done an incredible job with the new plant in JC. Product is flowing from there like water through a burst dam. The other plants that we've reopened are pouring out product also. I just wish I could help with the notebook problem."

"Thanks, Gerard. Ron?"

"Southeast is also doing great. Since two of the four plants that remain closed are in my region, we continue to be besieged by calls from former workers demanding to know when their plant is going to reopen. They've heard that other plants are going to a second shift and want to know why their plant couldn't have a first shift instead. They don't understand the economies involved and that it's less expensive to run one plant for two shifts than run two plants for one shift each."

"That's understandable," I said. "Those plants are important factors in their local economy. Roy Blu made the decision to keep them open and costing money rather than closing them down, but we can't afford to make that same mistake. I'm sure that some of the locals would like to have my head, but I have to consider the health of the overall company until everything settles down into predictable patterns. Bill?"

"Financially, the future looks very bright. It will be several months before payment money from new orders starts flowing in, but we're holding our own right now. The new plants are naturally a drain right now as production ramps up, but that situation will start to reverse in September when A/R's come due. With the exception of the four closed plants, every plant in the company should be considered to be operating solidly in the black."

"Thank you Bill. Ben?"

"As Ron mentioned, our biggest headache right now is the constant deluge of calls from furloughed employees. They are technically our people now, even if we did furlough them right after acquiring their plants, and we're bending over backwards to accommodate them. Anyone willing to move temporarily is being placed at another plant where we need people. We try to put them in the same job that they had before, but when we can't, we offer them the best we have. We're helping them with housing whenever we can, and with everything else they need, including finding schools and day care in the temporary locations."

"Thank you, Ben. Continue to do what you can. Tom?"

"I sort of feel guilty after hearing everyone's problems. My section has been rolling along smoothly ever since we caught up all of Mo Paper outstanding A/Ps. The news that we're now up to thirty-two paper plants has resulted in our business being actively sought by supplier representatives who wouldn't even take my calls a few years ago when we had just this one plant. I've even had a few calls from overseas suppliers who want to sell us chemicals and supplies by the shipload. Our suppliers see how fast we've been growing and want to continue to supply us as we grow. We have unlimited credit with all of them, and I'm sure we're getting about the best prices in the industry. I doubt that even Alliance is paying very much less for their chemicals and supplies."

I smiled. "That's a wonderful bit of good news. Thanks, Tom. John?"

"As some of you know, DD had to purchase an entire defunct print shop just to get a wire coil binding machine a week a go. When we began uncrating the stuff, we found a brand new 6130 in with it. After we set that up in Evansville, we also found the 4515 that we were expecting, and set that up. Three more 6130's arrived late Friday from the Lassiter plant and we set those up. So, by Saturday night we had all five binding machines operating in Evansville. Then we headed down to Little Rock, where we set up the remaining two new 6130s. Everything was going great guns when we left. I just wish I could pull another five 6130's out of a hat."

"As do I John," I said. "Thank you for your outstanding efforts this week. Matt?"

"As much as I hate to turn business away, I understand the need to refuse new MoPac orders calling for delivery in mid-August. If we can't deliver them, it would be far worse to disappoint customers after accepting their orders. Everything is moving along very well. Orders for Piermont products continue to increase as we slowly improve our market share, and Mo Paper products are through the roof right now."

"Thank you, Matt. Is there any other old business before we move to new business?"

When no one spoke up, I said, "Okay, new business. Matt, what are doing to appeal to youngsters, other than the construction paper?"

"What do you mean, DD?"

"I mean, what other products are you aiming towards that market?"

"None, right now. What did you have in mind?"

"I was thinking of perhaps a line of notebooks with cartoon characters on the cover. Or perhaps a line of inexpensive tracing paper, bound like a notebook; and perhaps perforated along the inner edge to make it easy to remove a sheet."

"Bound tracing paper for kids," Matt echoed as he thought.

"Maybe the covers on both front and back could have the cartoon characters on them?" Bill offered.

"Why just cartoon characters?" Gerard asked. "Why not notebooks with movie and television characters like Tarzan or the cast from Star Trek?"

"And something for the girls," Ben said. "How about Barbie, or Alice and the characters from Alice in Wonderland?"

"Wait a minute," Bob said. "We can't deliver the notebooks we have orders for now."

"I didn't mean for August delivery," I said. "I'm thinking about future sales, after the school store orders are handled. Christmas is coming. We should start thinking about it now. Merchants start placing their Christmas orders in August."

"I like it, DD," Matt said.

"And we should also start thinking about a new set of covers for the young adults and college kids once the flower power sales start to slump."

We continued to discuss the possibilities until the secretary at the front desk of the executive suite called to say that the special lunch I'd ordered from the B&B in town had been delivered.

"Lunch has arrived," I said as I rose to my feet, "but before we break to eat, there is one thing left to do. I'm the luckiest CEO of any company in America. It's not because of who my grandmother is, but because of the wonderful people that have helped me build this company. We're the envy of not only everyone in the paper business, but of every company in America. And it's all due to your efforts. You're the people who really make this company work and prosper. The time has come to reward one who has labored long and hard since the beginning. Effective immediately, John Fahey is our Vice-President of Production Engineering. Congratulations, John." I started the applauding and sat down so that John could stand up and speak.

John was a bit tongue-tied at first. He stammered a bit, then finally found his voice. "Thank you, DD. I- uh, don't know what to say. It's hard to believe that it's only been three years since that day you first entered the lobby downstairs and requested a tour of the plant. Piermont was on its last legs, and we were facing foreclosure within a fortnight. From information you picked up at Highland Lumber, you correctly assessed our situation and offered to step in if the price was right. You made an offer, Matt accepted, and the rest is history. You saved our plant and our town. This is my town. I was born here. I'll be eternally grateful for what you've done for us. It's been an honor to work with you for the past three years, and I hope that we'll have many more years together. I promise to give you everything I've got for as long as you want me here at Piermont. Thank you. Thank you everyone."

John's impromptu speech was so moving that everyone at the table just stared for a couple of seconds as he sat down, then burst into applause.

"Thank you, John," I said as the applause slowed. "You've always given a hundred and ten percent; just like everyone at this table. Now— anybody hungry?"

The lunch was delicious, as always. And like always it was a working lunch. We continued to discuss product ideas.

I had intended to head home to the ranch after the meeting was over at 3 o'clock, and had even notified Captain O'Toole of such, but I couldn't go and leave a major mess behind. It was my fault that we had orders for twelve million more notebooks than we could produce, and I had to find a solution. We were scheduled to leave for the Riviera on Thursday, so I had less than a week to resolve the crisis.

(continued in part 42 )

Many thanks to Bob M. for his excellent proofreading efforts on Chapters 36-45.

*********************************************

© 1999 by C. Sprite. All Rights Reserved. These documents (including, without limitation,

all articles, text, images, logos, and compilation design) may be printed for personal use only.

No portion of these documents may be stored electronically, distributed electronically, or

otherwise made available without express written consent of

StorySite and

the copyright holder.